About Stewart Udall

Who was Stewart Udall?

THE PUBLIC SERVANT WHO LED THE WAY FOR THE MOST IMPORTANT ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION IN OUR COUNTRY'S HISTORY

A CHAMPION OF OUR NATIONAL PARKS AND SCENIC BEAUTY

A FIERCE FIGHTER FOR RACIAL JUSTICE

A RENAISSANCE INDIVIDUAL WITH BROAD INTERESTS BEYOND THE ENVIRONMENT

AN ADVOCATE OF THE ARTS AND AND SUSTAINABLE URBAN DESIGN

THE FIRST PUBLIC OFFICIAL TO WARN AMERICA ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE

AN UNLIKELY STORY

“ An increasing Gross National Product has become the Holy Grail, and most of the economists who are its keepers have no concern for the economics of beauty." --Stewart Lee Udall, 1968

An increasing Gross National Product has become the Holy Grail, and most of the economists who are its keepers have no concern for the economics of beauty." --Stewart Lee Udall, 1968

“Above all, we must maintain the chance for contact with beauty. When that chance dies, a light dies in all of us, Thoreau said. We are the creation of our environment. If it becomes filthy and sordid, then the dignity of the spirit and the deepest of our values immediately are in danger.” –Udall, in a speech written for Lyndon Johnson, 1964

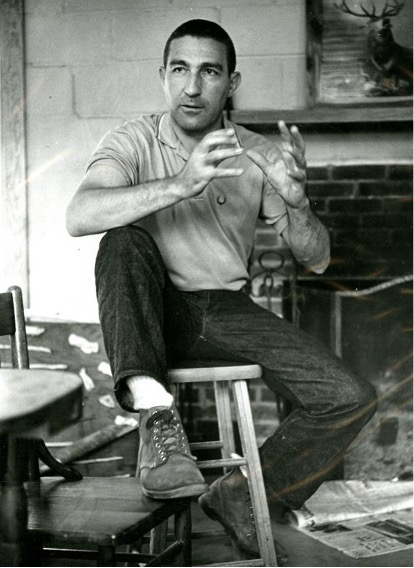

Stewart Lee Udall (1920-2010) served as Secretary of the Interior under both John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. During that time, he provided the political leadership for a legacy that includes the Clean Air, Water Quality and Clean Water Restoration Acts, the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the Wilderness Act, the Endangered Species List, the Highway Beautification Act, the Wild and Scenic Rivers and National Scenic Trails Acts, the Pesticide Reduction and Mining Reclamation Acts, the Solid Waste Disposal Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, the creation of a host of national parks and monuments, and other accomplishments many Americans now simply take for granted. Udall’s record is perhaps unmatched by any other Interior Secretary, and the Interior Department building in Washington DC is now named for him. So is the Easternmost point in the United States, Point Udall in the Virgin Islands. Yet most Americans know little of him.

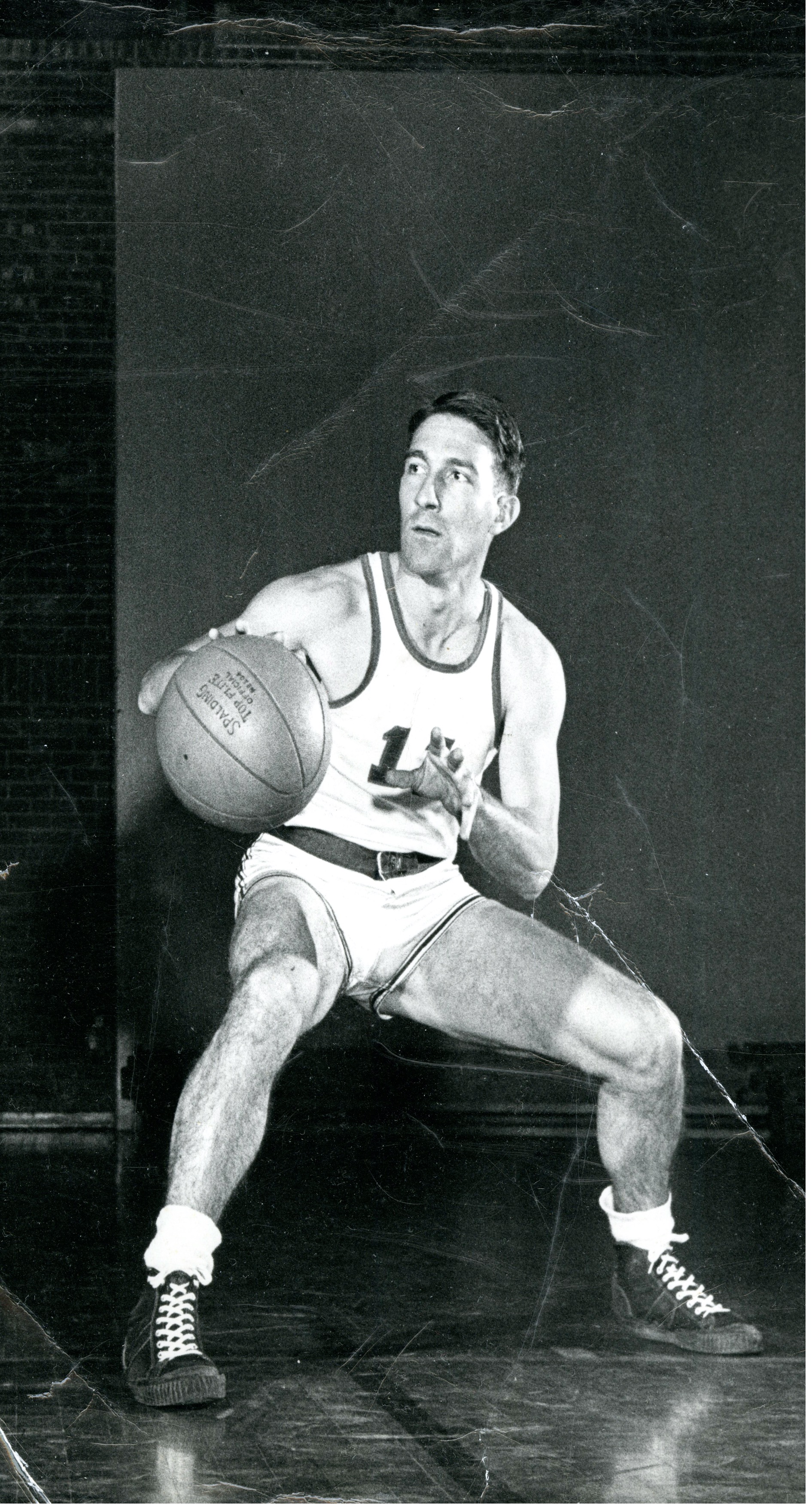

Advocate of racial justice and peace

Udall was much more than an environmentalist. He spoke out for peace and against the Cold War, traveling with poet Robert Frost to the Soviet Union to meet its premier, Nikita Khrushchev, to encourage weapons reductions. With his brother, Morris (Mo), he challenged racism at the University of Arizona, and later as a public official. With support from President Kennedy, he forced the integration of the Washington Redskins football team in 1962. When Udall discovered that the National Park Service had only one African American ranger (in the Virgin Islands), he directed the NPS to launch a major recruiting campaign in traditionally black colleges. Robert Stanton, the only African American director of the NPS, credits Udall’s effort as helping make possible his career as a park ranger. He still has the personal letter Udall sent him inviting him to become a park ranger at Grand Teton.

Udall was much more than an environmentalist. He spoke out for peace and against the Cold War, traveling with poet Robert Frost to the Soviet Union to meet its premier, Nikita Khrushchev, to encourage weapons reductions. With his brother, Morris (Mo), he challenged racism at the University of Arizona, and later as a public official. With support from President Kennedy, he forced the integration of the Washington Redskins football team in 1962. When Udall discovered that the National Park Service had only one African American ranger (in the Virgin Islands), he directed the NPS to launch a major recruiting campaign in traditionally black colleges. Robert Stanton, the only African American director of the NPS, credits Udall’s effort as helping make possible his career as a park ranger. He still has the personal letter Udall sent him inviting him to become a park ranger at Grand Teton.

Udall reshaped the Bureau of Indian Affairs to give more power to tribal organizations, appointing Oneida leader Robert Bennett as the first Native American to direct the BIA since the administration of Ulysses Grant. “Udall always took a back seat to Indian leaders,” says Diane Humetewa, a Hopi and the first Native American federal judge. In 1966, Udall froze the federal transfer of lands to the state of Alaska to ensure that Alaska Natives would not lose their lands. As William Hensley, an Alaskan Native leader, later wrote, “Udall, with his sense of fairness, used his power to help establish the most generous land settlement in American history… discarded the overlordship of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and provided 40 million acres of land and nearly a billion dollars for Native Alaskans to manage, invest and utilize for all time to come. His generosity of spirit, fair-mindedness and love for the land will never be forgotten…[but he] was reviled by those in Alaska who would have bulldozed away Native claims.”

A leader with broad interests

Udall was a prolific writer and speaker, authoring dozens of articles and nine books, including his noted 1963 environmental wake-up call, The Quiet Crisis. A lover of outdoor adventure who climbed Japan’s Mt. Fuji and Africa’s highest peak, Kilimanjaro, while Interior secretary, he was referred to in African newspapers as “the most vigorous member of the vigorous New Frontier.” But he was also an advocate of the arts and humanities, and championed national endowments for both during the 1960s. “We have, from the beginning, underestimated the arts in this country,” he wrote in 1964, “and we now run the risk that we shall become so preoccupied with technology, the uses of military and economic power, physical power and prosperity, that the things of the spirit will not prosper.” Americans did not recognize, he added “the difference between meaningful art that ennobles or elevates and entertainment that distracts.”

Udall was a prolific writer and speaker, authoring dozens of articles and nine books, including his noted 1963 environmental wake-up call, The Quiet Crisis. A lover of outdoor adventure who climbed Japan’s Mt. Fuji and Africa’s highest peak, Kilimanjaro, while Interior secretary, he was referred to in African newspapers as “the most vigorous member of the vigorous New Frontier.” But he was also an advocate of the arts and humanities, and championed national endowments for both during the 1960s. “We have, from the beginning, underestimated the arts in this country,” he wrote in 1964, “and we now run the risk that we shall become so preoccupied with technology, the uses of military and economic power, physical power and prosperity, that the things of the spirit will not prosper.” Americans did not recognize, he added “the difference between meaningful art that ennobles or elevates and entertainment that distracts.”

The University of Colorado’s Patty Limerick, an expert on the history of the West, argues that, “Of all the people who have served the United States in an executive capacity, only Thomas Jefferson exceeded Stewart in so successfully applying all of his varied interests and skills in service to America.” Limerick also credits Udall with his own contributions to western history, especially in his book, The Forgotten Founders. His view was that the real heroes of the West were unsung settlers—Indians first, then Hispanics and whites who came to build communities and tend the earth, not the gunslingers and cavalrymen of lore.

Urban renewal and Revitalization

Stewart Udall sought to revitalize America through what he called “the economics of beauty.” Encouraged by him, Lyndon Johnson warned that we were losing America’s natural beauty and could soon become an “ugly America.” As historian Douglas Brinkley explains, Udall was even more focused on America’s urban environment, advocating a full-scale revitalization of our cities, stressing racial justice, neighborhood parks, public transportation and significant reductions of pollution, poverty and sprawl, a view he elaborated in his 1968 book, 1976: Agenda for Tomorrow. His love for beauty and the arts was shared by his wife Lee, as former aide Boyd Finch points out in Legacies of Camelot. We need a plan “to make all cities cathedrals for everyday existence,” Udall wrote, “a plan that envisions full employment as the humane use of human beings, not merely more jobs.”

Stewart Udall sought to revitalize America through what he called “the economics of beauty.” Encouraged by him, Lyndon Johnson warned that we were losing America’s natural beauty and could soon become an “ugly America.” As historian Douglas Brinkley explains, Udall was even more focused on America’s urban environment, advocating a full-scale revitalization of our cities, stressing racial justice, neighborhood parks, public transportation and significant reductions of pollution, poverty and sprawl, a view he elaborated in his 1968 book, 1976: Agenda for Tomorrow. His love for beauty and the arts was shared by his wife Lee, as former aide Boyd Finch points out in Legacies of Camelot. We need a plan “to make all cities cathedrals for everyday existence,” Udall wrote, “a plan that envisions full employment as the humane use of human beings, not merely more jobs.”

What truly stands out about Udall is the contemporary relevance of all that mattered most to him and moved him to action. The guardian of our public lands, he was even more concerned with urban problems and with social and environmental justice. The “national sin of racism” that he wrote of during the 1960s riots that rocked American cities, has re-emerged sharply in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Global warming, about which he warned more than 50 years ago, has struck us with a vengeance. Warmer winters, record summer heat, intense weather events and massively destructive fires, as well as the melting polar ice Udall predicted, are all part of our lives now. The “doomsday clock” of the Atomic Scientists. representing the threat of nuclear weapons. is the closest to midnight it has ever been. Our parklands and open space have not kept pace with rushing population growth, and automobile congestion grips our cities and suburbs. Now, as then, Udall would have called attention to the fact that the harshest of our environmental problems fell on the poor and minorities. Udall’s story and his warnings remind us not to ignore our Cassandras; they have too often been right.

An unlikely story

As we learn from biographer Thomas G. Smith, Udall’s was an unlikely life path for the son of a Mormon rancher, bishop and attorney. He grew up in the height of the Great Depression, without electricity and running water, in St. Johns, Arizona, an isolated desert hamlet on the Little Colorado River. His brother, U.S. Representative Mo Udall, called St. Johns, “a town so small you could put the Entering and Leaving signs on the same post.” Its current mayor is still a Udall. Many of Udall’s fellow students in St. Johns were Hispanic or Native American and he grew to deeply appreciate their cultures.

“Of all the people who have served the United States in an executive capacity, only Thomas Jefferson exceeded Stewart in so successfully applying all of his varied interests and skills in service to America.”

- Patty Limerick, historian and director of the Center of the American West.

The Highlights of Stewart Udall's Life

One,

Two, ThreeGetting involved is easy.

Step 1: Donate

Contribute now to help optimize the impact of this important film!Your support will help us inspire more audiences to work with their communities to achieve environmental & social justice goals.